Read more below

Sri K. Pattabhi Jois studied for over 35 years (1927-1953) with his Guru T. Krishnamacharya, and from this study, as well as from holy texts, his own practice, and teaching thousands of students, he is spreading his knowledge of Ashtanga Yoga. Sri K. Pattabhi Jois founded the Ashtanga Yoga School in 1948 in Mysore, India, originally named Ashtanga Yoga Nilayam: the traditional, 8-limbed yoga research institute in the lineage of T. Krishnamacharya and Rishi Patanjali. It has since been re-named as the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute and in 2008 Krishna Pattabhi Jois Astanga Yoga Institute (KPJAYI).

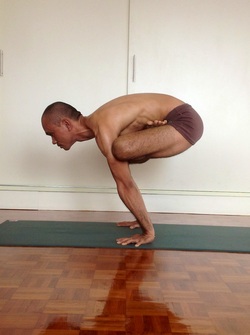

Ashtanga Yoga is often defined as an intense, athletic, and dynamic form of yoga. In many ways this is true, though Ashtanga does much more than strengthen and stretch the body. By practicing with awareness of the breath, the drsti (gazing point), and the bandhas (energy locks), one can develop a sense of consciousness in both the body and the mind. According to Sri K. Pattabhi Jois, Ashtanga Yoga is a path that leads us to the spirit that resides in all of us, and is in fact our very nature.

Reading and studying the philosophy of yoga found in ancient, holy texts, is only a fraction of the practice. Books can show us the path of yoga, but practical training is the only way to clean out the body and mind from the blockages and to activate the physical, mental, and spiritual renewal the leads to freedom and happiness. Sri K. Pattabhi Jois says Ashtanga Yoga is 99% practice, and 1% theory.

In Ashtanga practice, the breath (ujjayi breathing), asana (posture), vinyasa krama (vinyasa-technique), bandhas (muscle and energy locks) and drstis (gazing points) are all used in conjunction with one another, which acts to deeply warm the body, making it safe, and wonderfully intense. The inner heat generates a cleansing process that affects everything from the organs, to the muscles, to the nervous system, to the mind and spirit.

Ashtanga yoga's asanas open up the body naturally and safely. The "ujjayi" breathing, the slow and prolonged rhythm of the movements, the pulling together of the bandhas, and the heat generated in the body all lower the risk of injury. Though despite this, one should still remember to avoid using too much strength or force in the postures, otherwise it may actually be dangerous to approach the more strenuous asanas. One should also not be too eager in the practice, as that can also lead to injury. Listen to your body; it will tell you where the limits are, and where they are not. For example, you can continue to stretch forward even if you feel tight, simply try to release the muscle's tension through the breath and a deep relaxation. If you reach a sensation of pain, go back a bit. It will come when it is ready. We are not meant to perform the asanas in exactly the same way every day, some days will be deep and open, and other days will feel tight and heavy. Again, listen to your own body and learn to trust what it is saying to you.

Instructions for practice

To really benefit from and support your asana practice, try to create the best possible conditions in which to practice. This pertains to both the external and internal factors that could affect your concentration and general attitude or mood.

If you are just beginning, it is strongly suggested that you find a place to study with a professional teacher, preferably in a yoga shala (yoga center or room) that teaches the traditional Mysore practice. It is always best to begin the practice under the supervision of an experienced teacher, or guru, as they can best assure of your development and understanding of the practice. Books can introduce the asana yet cannot replace a teacher, as they simply cannot see you or understand issues or needs specific to you.

The best time to practice is in the morning, when the air is richest in "prana" (life-giving energy), the mind has not yet become activated with excessive thought, the body is rested, and the stomach is empty. Morning practice will open and energize the body and mind for the rest of the day. On the other hand, know that it can take time to become accustomed to a morning practice, and the body is often more stiff in the morning than in the evening. Evening practice is also acceptable (although traditionally there is no practice after the sunset) if it suits your rhythm or schedule better, or simply if it feels better.

It is not a goal within the practice of ashtanga yoga that you forget the outside world, and develop an obsessive attention on the inner world of your own body and mind. Avoid the appeal of fanaticism. Yoga should be a source of support and strength for your everyday life, and improve the quality of your life on all levels. In regards to how many poses you should perform, or how frequently you should practice, listen to your inner thoughts and feelings, listen to the reality of your life, and the reality of your body, and this should help you decide where to stop and how much to practice. And of course, if you are practicing in a yoga shala, your teacher will be the best guide and partner in this practice as it develops and grows. Traditionally, the practice is done six mornings per week, with Saturday as a day of rest. Rest days are also taken on the full and new moon and on holidays; and for women, the first three days of menstruation, the first three months of pregnancy, and the first three months post-childbirth. Though if it is possible for you to follow the traditional recommendation and practice six times a week (even if some days your practice is shorter), a cleansing process occurs, the asanas develop, the mind becomes clear and full of energy, and the practice falls into a daily rhythm.

Ashtanga yoga is beneficial for anyone interested; the stiff and the flexible, the fit and the unfit. You practice at your own level and in your own timing, listening to your own body, your own breath, and mind. To stay motivated in the practice, it is important that you develop at the right pace for you, moving forward at a calm and steady pace. It is important to resist the desire to compare oneself to others, as everyone benefits from the practice in their own way.

It is to be expected that after some time, the practice will bring about a positive change in the student's body and mind, and even lifestyle choices as in diet, and overall approach to health. As the student's trust in the practice grows, the practice develops naturally. Students often find that the biggest obstacle along the way is not, for example, inflexibility in the body or weakness in their muscles, but is rather an inflexibility of mind.

In an odd kind of "double-edged sword", often, the more you advance in the practice, the less you obsess with a need to achieve. Patience is cultivated. Small steps forward, both physical and psychological, erase doubt and give you energy to continue along the path. Try to take note of your progress, at the same time that you give yourself permission to "regress", as progress doesn't always to go in a forward direction. For example, at certain times it may be useful to stay in the asanas longer than 5 breaths (even up to 80 breaths), certainly when you are just learning, but even when you are further along in your practice and experience intense soreness or changes in your body. It can be necessary at times to go "backwards" in order to restore the body's energy balance. With the right attitude, yoga is a certain path towards meeting your true self, where one is happy and already content with life as it is.